Winemakers Are Building Houses for Bats to Make Vineyards Greener

Attracting the right species can help get rid of vine-munching insects and allow farmers to cut back on pesticides

By Jennifer Nalewicki

smithsonian.com

August 24, 2015

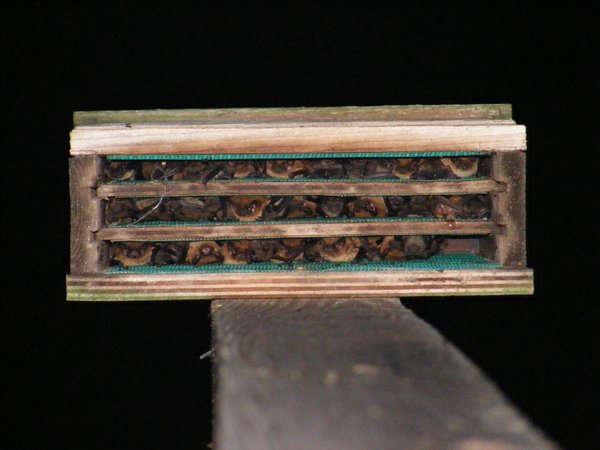

A bat box stands over the Herdade do Esporão vineyard in Portugal. (Courtesy of Esporão/Francisco Rivotti)

As the sun sets in the Alentejo, a wine-producing region about 100 miles southeast of Lisbon, dozens of bats leave their shelters and take flight, their dark bodies in stark contrast to the brilliant pinks and oranges of dusk. It’s dinnertime for the nocturnal creatures, and the winemakers at Herdade do Esporão are banking on the flying mammals to help rid the vineyards of unwanted visitors.

So far, it looks like the partnership is paying off—Esporão has seen a drop in the number of vine-gobbling insects wreaking havoc on its 1,235 acres of wine grapes. As a winery striving to make its operations as sustainable as possible, the bats have become a reliable replacement to the harsh chemicals often used to ward off pests.

Bats have been assets to the wider agricultural community for decades, with many farmers relying on these “wingmen” to kill insects instead of using an overabundance of pesticides and other harmful chemicals. Depending on the species, bug-eating bats can devour between half to two-thirds of their body weight in insects each night—equivalent to about 1,000 bugs an hour.

In the United States alone, bats save the agricultural industry anywhere from $3.7 billion to $53 billion each year in pest-control services, according to a study conducted by the U.S. Geological Survey. However, it’s only been in the last few years that wineries have implemented specific bat-friendly practices within their estates.

At Herdade do Esporão, biologist Mário Carmo is in charge of the bat program, which began in 2011. No bats previously lived on the property, Carmo says, probably due to the lack of shelter in a landscape comprised of rolling plains punctuated by the occasional stand of cork oak trees. Bats prefer habitats that are warm, dark and well protected from predators, according to the nonprofit Organization for Bat Conservation, so it’s not surprising that the creatures had bypassed the vineyard for better accommodations in the form of bridges or attics.

“[The lack] of possible homes for the natural establishment of bats reinforced the importance of this project, which is to help restore the balance of [the estate’s] ecosystems,” Carmo says. “We decided to attract bats to our property and use them as allies in pest control in the vineyards, due to the type of agriculture practiced on the property.”

The estate installed 20 wooden bat boxes amid its rows of Verdelho, Touriga Nacional, Antão Vaz and other indigenous grape varietals. As of this August, the boxes house some 330 bats, including the Kuhl’s pipistrelle, a native species common in southern Europe, and the lesser noctule, or Leisler’s bat, a species found across the continent.

David Baverstock, chief winemaker at Esporão, was one of the first proponents of the bat program. He says that sustainability plays a big role in all areas of the winery, from grapevine to wine bottle. Although Esporão isn’t 100-percent organic, about one-third of its vineyards are dedicated to organic farming, and pesticides and industrial fertilizers are prohibited in those areas. In addition to bats, the vineyard turns to ladybugs and the great tit, an insect-eating bird, as forms of natural pest-control.

“Bats aren’t the only replacement, but they’re one of the elements that make [sustainable farming] possible,” says Carmo. “In terms of diseases in the vineyards, we more or less have that under control, but insect pests are our main concern, and the use of bats is one of those alternatives.”

Carmo doesn’t yet have specific percentages for how much the bats have contributed to pest control on the property. Currently, he’s working with the Centre in Biodiversity and Genetic Resources at the University of Porto to study genetic material in guano taken from the bat boxes to discern which insects the bats are eating.

In an email, Carmo surmised that the bats were helping to kill off the European Grapevine Moth (Lobesia botrana), considered a major vineyard pest throughout Europe and, more recently, in California. However, he says he won’t be certain until he receives the analysis.

“[The results] will most likely indicate that, like everything in life, there will be a balance between the pest species and the auxiliaries or insects that eat the bad insects,” Carmo says. “But because bats don’t eat only the bad [bugs], but also the good ones, it helps keep a balance of insect populations.”

Rob Mies, executive director of the Organization for Bat Conservation, says that even if bats do munch on some of the good insects, they still play a pivotal roll in agriculture, and the benefits of having them around far outweigh the negatives.

“Even if bats ate a particular insect species down to a certain density, they wouldn’t waste their energy to eat the last remaining few,” he says. “Instead, they would switch to a different type of insect.”

Getting involved in winemaking carries benefits for the bats, too. The flying mammals are no strangers to bad publicity, often being cast as the blood-sucking bad guys lurking in the shadows.

“I think the reason people are so fearful of them is because bats are nocturnal, and humans have a natural fear of night, since our vision isn’t the best at that time of the day,” says Mies. “In many stories and movies, nocturnal animals have been portrayed as evil.”

To add injury to insult, in recent years, bats’ numbers have been threatened due to the increase in wind turbines, which bats can accidently fly into, as well as the spread of white-noise syndrome, a lethal disease that manifests as a white fungus on bats’ skin.

Bat programs like the one at Esporão, might help more people see bats as friends rather than foes and improve conservation efforts. Esporão already has plans to double its collection of bat boxes, and although visitors to the estate can’t see the nocturnal creatures in action, they can see the prominent roosts as they walk through the vineyards.

“If we talk to [people] and try to explain that the presence of bats will reduce the usage of pesticides and chemical fertilizers,” Carmo says, “I think it’s enough to convince them that this is the right thing to do.”